![]()

The

man known as "Bruno," pen name "Max Sartin," died in

Salt Lake City this past November 23, age 93. He was cremated without service

of any kind, not even an atheist service. His friend Robert D' Attilio published

an obituary in the January-February issue of L'Internazionale, the Italian

anarchist journal. Therefore we can presume that the secret police in Rome

have closed a file that has been open since the early Mussolini years.

But in the United States, where Bruno lived and died, where his greatest

work was done, not a single public word about his death has been said. The'

present obituary is the first to appear. Possibly the FBI, CIA, and' red

squads of several cities and states already know about Bruno and his activities

and his death. But very likely they are learning only now. They're learning

that if the federal government never did succeed in stamping out Sacco and

Vanzetti's ultrarevolutionary sect-if that sect continued to agitate long

after the 1927 executions in Massachusetts-if the sect went on to produce,

completely unknown to other Americans, heroes and martyrs in the revolutionary

struggle for liberty in Spain and Italy-if the sect managed in fact to continue

its unyielding propaganda into the 1980s-the reason was Bruno. Other comrades

played great roles, but Bruno was foremost. He cannot be called a leader.

God forbid that an anarchist -group should have a leader! He was merely,

let us say, principal militant. And if the government authorities are learning

this only now, the reason is because for a period of no less than 59 years,

Bruno lived in conditions of revolutionary clandestinity. The underground

man: it was Bruno.

People who have known something about him never said his real name in public. For seven years I wanted to write his story, but his friends and acquaintances pleaded with me not even to approach the man because of the fright it would cause him. Paul Avrich, the distinguished historian of anarchism, tried to introduce himself to Bruno 15 years ago at a memorial meeting for Emma Goldman- Bruno was one of several elderly Italians in attendance and the old revolutionary fled the room in terror at being recognized by a stranger. So his secret was kept out of respect for his advanced age. Also out of realistic fear for what the FBI or the Immigration Service might do. But the time has come. His real_name was Raffaele Schiavina. He was fair, pleasant-looking, neatly dressed, very dignified with a gray mustache. He looked bourgeois. And his story can only be told the long way, beginning in Italy in the 1880s. A lawyer named Luigi Galleani hated the law and took up the cause of the working class. Fearing arrest, Galleani fled to France and went to work for proletarian revolution. France deported him.

He went to Switzerland and arranged a celebration to honor the Haymarket

Martyrs of the United States. Switzerland deported him. He returned to Italy,

was arrested again, served a prison term, was sent to the penal isle of

Pantelleria in the Mediterranean and escaped to Egypt. Luigi Galleani turned

up in Paterson

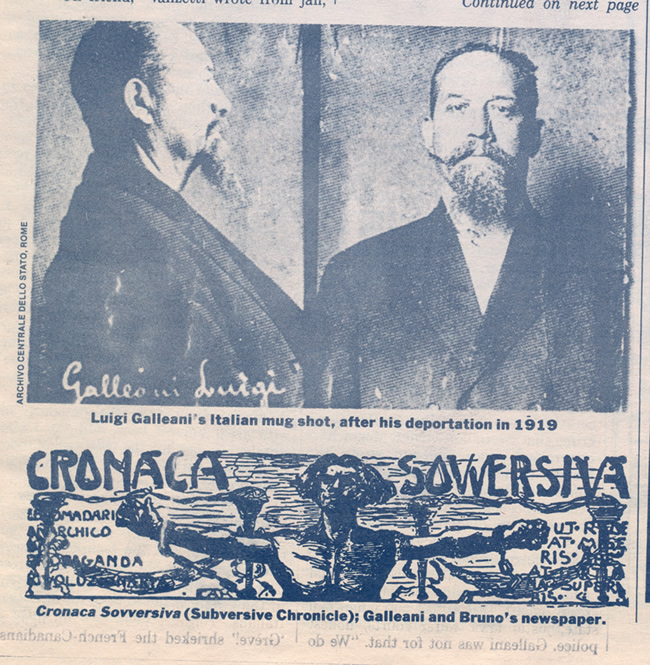

New Jersey, in 1901. A strike broke out among the exploited Italian-American. silk workers. He threw himself into their cause. He orated, agitated, wrote, and when a shoot-out occurred between police and workers, Galleani was shot in the face. (Not in the back - not Luigi Galleani!) Again he was indicted. He fled to Canada, then smuggled himself back into Vermont. He settled in Barre among the exploited Italian-American quarry workers. Under the name "Luigi Pimpino," he founded a revolutionary newspaper called La Cronaca Sovversiva, or The Subversive Chronicle. A few years later he moved La Cronaca Sovversiva to Lynn, Massachusetts.

The newspaper acquired readers not only in the United States but in Italy and around the world wherever Italian emigration was large. Above all, though, Galleani's influence was local. He spoke in a lilting tremolo voice, and there was something about him that caused young men (his followers seemed almost always to be men) in the Little Italies of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New England to swear a nearly personal allegiance. He was the "Maestro," the "capo historico" of Italian-American anarchism, as Giuseppi Fiori has described him in a recent book. And among those young men was Raffaele Schiavina, or Bruno. Bruno went to work as La Cronaca's administrator. He became Luigi Galleani's lieutenant. He never ceased being it.

Galleani's doctrine constituted, in the title of a New York newspaper of the 1890s, It Grido degli Oppressi, "The cry of the Oppressed." Galleani said that, under the capitalism that existed at the turn of the century, workers were slaves. If they formed unions, police pulled out guns. If they went to court, judges hanged them. If they pleaded to the priests, the priests damned them. The state, the church, the prevailing morality - all conspired to keep the workers in poverty. And when he delivered this message to the Italian-American toilers in Paterson, Barre, and the mill towns of Massachusetts, there was a reason why people listened, and why small but significant numbers of them applauded. Galleani called for society to take over the capitalist economy. He was in this sense a socialist. But there are socialists and socialists. Ordinary socialists, the electoral social democrats, favor gradual reforms, a less greedy capitalist class, a more paternal state, juster laws, fairer courts, honest police. Galleani was not for that. "We do not argue about whether property is greedy or not, if masters are good or bad, if the state is paternal or despotic, if laws are just or unjust, if courts are fair or unfair, if the police are merciful or brutal," he said. "When we talk about property, state, masters, government, laws, courts, and police, we say only that we don't want any of them." Galleani stood to the left of the social democrats. He was an anarchist. But there are anarchists and anarchists. The anarchist trade unionists - the anarcho-syndicalists or Wobblies - wanted unions that would fight for better conditions in the here and now, while still preparing revolution for the future. The anarcho-syndicalists dreamed of libertarian unions administering the whole society in the interest of everyone. Galleani was not for that. He thought that trade unions were instruments of compromise. He stood to the left of the anarchosyndicalists. His own doctrine was anarchist-communism. But there were anarchist-communists and anarchist-communists.

Mainstream anarchist-communists favored a militant organization of committed anarchists to lead the workers to the uprising. Galleani was not for that. He thought that any organization at all was an instrument of oppression, for every organization has leaders and followers, and leaders are invariably oppressive and corrupt. He stood to the left of mainstream anarchist-communism. His position was anarchist-communist antiorganizzatrice. He favored unorganized action by individual anarchist militants to spark the armed insurrection of the masses. Further left than Luigi Galleani, no man or woman has ever gone. It was spontaneous revolution that he pictured, planless, impassioned, the way Upton Sinclair described a cordage strike at Plymouth, Massachusetts. Bartolomeo Vanzetti, that militant Galleanista, was there. It was 1916: "On Thursday morning, payday, one of the men in number three spinning-room got into a dispute with his foreman; the foreman told him to take his coat and hat and get out, and instead of obeying, the man turned and started yelling to his comrades. The foreman took him by the shoulder to put him out, and others came rushing to his help, and there was a tumult, and above it rose the word, 'Strike!' It spread like wildfire down the long spinning-room; what had been at one moment an industry became in the next a mob. 'Sciopero!' yelled the Italians. 'Folga!' echoed the Portuguese. 'Greve!' shrieked the French-Canadians. 'Streik!' bellowed the Germans. And 'Strike! Strike! Strike!' roared Americans and English and Irish and Welsh, and all others who had learned the word. A hundred Paul Reveres set out in every direction, spreading the wildfire from room to room. Until finally the company detectives started pushing their way through, asking, "Who is that wop they call Bart - the one with long mustaches like a walrus?" Because a spontaneous uprising is fine and good, but it always helps to have antiorganizzatori in the crowd. The wop named Bart helped lead the big cordage strike in 1916. He wrote his reports and sent them to Bruno and Galleani at La Cronaca Sovversiva, and then he was blacklisted and there were detectives after him.

Galleanisti were consumed with an ideal. It was a vision that men and women, without a state to rule them, without capitalists to exploit them, without priests to fill them with lies, without all these obstacles and enemies, could finally flower into the fullest potential of humanity. A vision that workers could undertake to organize their own work, and not have to listen to bosses. A vision that communities could organize themselves, and federate voluntarily with other communities. It was a belief that, under conditions of self-government and individual liberty, man's best instincts would come forward. People would be generous. They would be sensitive. They would appreciate beauty, art, poetry. It was a grand vision. It went beyond the usual left-wing or reformist talk of dollars and laws and a fairer slice of the pie. The anarchist vision spoke of the important things: the beauty that life can have when individuals are free to control their destinies, the possibility that ordinary workers can be free creators, not drones. That everyone can enjoy the kind of life lived by the elite. If only we were free of exploiters, and of ignorance, and of tyrants! If only "everything belonged to everyone," which was Galleani's fundamental economic concept.

In a sense, leftists of every stripe have shared that vision, usually as a kind of harbor light of social values. Galleani's version differed only because he took it literally as prophecy of what would occur tomorrow - not the day after. To be a Galleanista was to wander through life drunk with this expectation. It was to blink from the sun that was about to rise. It was to feel exalted with revolutionary expectations. It was practically to be in love.

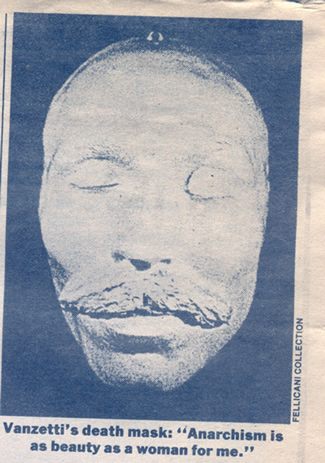

"Oh friend," Vanzetti wrote from jail "the anarchism is as beauty as a woman for me, perhaps even. More, since it include all the rest and me and her. Calm, serene, honest, natural, vivid, muddy and celestial at once, austere, heroic, fearless, 'fatal, generous, and implacable-all these' and more it is." They were, of course, fanatics. But fanaticism made them saints. Self-perfection was a revolutionary method. Bruno translated into English Galleani's theory of anarchist self-perfection: "We, our selves, have to start the revolution from within ourselves, by discarding old superstitions, selfishness, self-imposed ignorance, foolish vanities, and moral deficiencies." They did discard. "And, when, through experience, we have become worthy of the cause, we will be able to arouse the same need of moral elevation and freedom that will spread in an ever-widening concentric movement, reaching those groups furthest from us, like the effect of a stone cast into a pond." Dreams? The theory proved true. Vanzetti was arrested together with Nicola Sacco - and slowly the world realized that Bart and Nick were not like other people. They were better. They were exactly the way Vanzetti described anarchism: calm, serene, honest, natural, vivid, muddy and celestial at once, austere, heroic, fearless, fatal, generous, and implacable. They possessed personal grandeur. And as news of their astonishing traits spread, so did the movement in their defense. That is why in literature, too, Galleanisti made their mark on American life, why John Dos Passos was always peopling his chronicles with thick-accented anarchist saints, why Upton Sinclair wrote Boston, why Edna St. Vincent Millay and Countee Cullen and so many others sang of Sacco and Vanzetti.

Did the Galleanisti do more than orate and publish

and lead strikes? We cannot be sure. Bruno, as administrator of Cronaca

Sovversiva, was in an exposed position and not likely to have engaged in

the kind of individual acts that his own doctrine called for. But he and

Galleani knew what kind of environment they were generating. Robert D'Attilio,

the shrewdest and most thorough authority on the Sacco-Vanzetti affair,

has revealed that one of the pamphlets advertised in La Cronaca's columns,

"La Salute e in Voi" ("Health Is Within You"), was not,

in fact, a health pamphlet. The pamphlet was included in the "Library

of the Social Studies Group" distributed by the Gruppo Autonomo di

East Boston, but it was not exactly a social study. It was written by a

comrade who later became Professor of Chemistry at the Milan Polytechnic. And without question, somebody

mailed two dozen letter bombs in April 1919 addressed to John D. Rockefeller

and a series of government officials, almost every one of whom had engaged

in persecutions of La Cronaca Sovversiva. Somebody mailed a bomb to Attorney

General A. Mitchel Palmer, the most maniacally antilabor attorney general

in American history. Somebody planted the eight bombs that went off in June

1919, not to mention the further bomb that blew the front off the attorney

general's. home. Were these somebodies police agents? Anarchists? A combination

of the two? The last of those explosions went off too early, and one of

the somebodies was blown up so atrociously that part of the body landed

across the street on the front step of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin

D. Roosevelt's house. Roosevelt found leaflets saying, "Long live social

revolution! Down with tyranny!" and from body parts and remnants of

a polkadot tie, a probable identification was made to Carlo Valdinoce, Paterson

anarchist, associate of Sacco and Vanzetti's, former editor of La Cronaca

Sovv€rsiva. A battle was going on, Galleanisti on one

Professor of Chemistry at the Milan Polytechnic. And without question, somebody

mailed two dozen letter bombs in April 1919 addressed to John D. Rockefeller

and a series of government officials, almost every one of whom had engaged

in persecutions of La Cronaca Sovversiva. Somebody mailed a bomb to Attorney

General A. Mitchel Palmer, the most maniacally antilabor attorney general

in American history. Somebody planted the eight bombs that went off in June

1919, not to mention the further bomb that blew the front off the attorney

general's. home. Were these somebodies police agents? Anarchists? A combination

of the two? The last of those explosions went off too early, and one of

the somebodies was blown up so atrociously that part of the body landed

across the street on the front step of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin

D. Roosevelt's house. Roosevelt found leaflets saying, "Long live social

revolution! Down with tyranny!" and from body parts and remnants of

a polkadot tie, a probable identification was made to Carlo Valdinoce, Paterson

anarchist, associate of Sacco and Vanzetti's, former editor of La Cronaca

Sovv€rsiva. A battle was going on, Galleanisti on one side, the Department of Justice on the other. La Cronaca Sovversiva came

out against World War I with the slogan: "Against the war, against

the peace, for the social revolution." That was the government's moment.

In July 1918, La Cronaca Sovversiva was legally, or rather illegally, suppressed

(though two issues managed to come out clandestinely the next year). Government

agents seized the newspaper's files. Bruno served a year in jail for antiwar

activity. Then came the deportations. D' Attilio has discovered a secret

memo drawn up by the Department of Justice and the Bureau of Immigration

in which any connection at all to La Cronaca Sovversiva was cited as ground

for deportation. Bruno and Galleani and seven other comrades were expelled

to Italy in June 1919, three weeks after the attorney general bombing. Less

than a year later, Andrea Salsedo, Brooklyn typesetter, close friend of

Galleani's, was tortured in Department of Justice offices on Park Row, New

York, and mysteriously fell from the 14th floor. It was two days later,

as part of the same federal mop-up, that Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested

and accused of staging a payroll holdup and murder at South Braintree, Massachusetts

- a crime that Sacco conceivably might have committed, since Galleani wrote

eloquently in favor of

side, the Department of Justice on the other. La Cronaca Sovversiva came

out against World War I with the slogan: "Against the war, against

the peace, for the social revolution." That was the government's moment.

In July 1918, La Cronaca Sovversiva was legally, or rather illegally, suppressed

(though two issues managed to come out clandestinely the next year). Government

agents seized the newspaper's files. Bruno served a year in jail for antiwar

activity. Then came the deportations. D' Attilio has discovered a secret

memo drawn up by the Department of Justice and the Bureau of Immigration

in which any connection at all to La Cronaca Sovversiva was cited as ground

for deportation. Bruno and Galleani and seven other comrades were expelled

to Italy in June 1919, three weeks after the attorney general bombing. Less

than a year later, Andrea Salsedo, Brooklyn typesetter, close friend of

Galleani's, was tortured in Department of Justice offices on Park Row, New

York, and mysteriously fell from the 14th floor. It was two days later,

as part of the same federal mop-up, that Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested

and accused of staging a payroll holdup and murder at South Braintree, Massachusetts

- a crime that Sacco conceivably might have committed, since Galleani wrote

eloquently in favor of expropriations, but that most likely he did not commit. Vanzetti's innocence

was as certain - as these things can be. Then began seven years of legal

prosecutions that were so distorted with bigotry against immiants, Italians,

and radicals, so contemptuous of justice and fair play, so filled with the

venom of class hatred, that stinks and odors from the trial hovered over

Massachusetts for half a century afterward, until finally a governor brave

enough to acknowledge truth issued a formal proclamation repudiating the

trial and lifting all taint of guilt from the executed anarchists. Fifty

years it took! The signature at the bottom said Michael S. Dukakis.

expropriations, but that most likely he did not commit. Vanzetti's innocence

was as certain - as these things can be. Then began seven years of legal

prosecutions that were so distorted with bigotry against immiants, Italians,

and radicals, so contemptuous of justice and fair play, so filled with the

venom of class hatred, that stinks and odors from the trial hovered over

Massachusetts for half a century afterward, until finally a governor brave

enough to acknowledge truth issued a formal proclamation repudiating the

trial and lifting all taint of guilt from the executed anarchists. Fifty

years it took! The signature at the bottom said Michael S. Dukakis.

The federal campaign against anarchist-communist antiorganizzatori was large, sustained, ruthless, illegal, violent. By the early 1920s, there was reason to suppose this campaign had succeeded. Galleani and Bruno were gone, the newspaper was closed, the files were seized, one militant had blown himself up, another was defenestrated, and two others, guilty or innocent, were on the road to the electric chair. Galleani's movement appeared to have been wrecked.

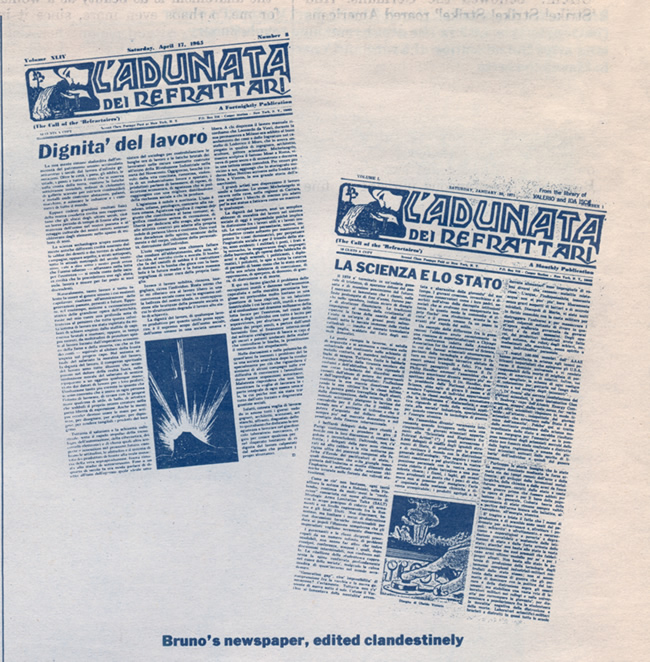

But the Galleanisti were very tough. LaCronaca Sovversiva didn't die. Galleani and Bruno revived it in Turin: Then Mussolini came to power and Galleani's troubles began all over, He was arrested on a sedition charge, jailed, arrested again, banished to an island off Sicily, jailed again, this last time for the crime of insulting Mussolini. Finally he was placed under house arrest. He died in 1931, age 71, still under police surveillance. Bruno fled to France, He published an Italian-language anarchist newspaper, Il Monito, in Paris. He undertook to raise a European defense of his imprisoned American comrades. And from Paris he observed the long, painful progress of the world movement on Sacco and Vanzetti's behalf, the movement's success at revealing class bias in Massachusetts, its failure at saving the comrades, then the astounding grace and nobility with which the martyrs met their fate. Meanwhile the surviving comrades in America - they called themselves the tribu or the tribe - founded a new newspaper to replace La Cronaca Sovversiva. It was called L'Adunata dei Refrattari, which literally translates as "The Call of the Refractories" and means something like "The Call of the Incorrigibles." L'Adunata dei Refrattari was published in Newark and New York. The newspaper brought out a volume of Galleani's writings, La Fine dell'Anarchismo? But publishing a newspaper was difficult. The surviving Galleanisti in America were workingmen in the shoe-making, cigarmaking, coal-mining, garment, stonequarry and other trades. They weren't journalists. They needed skilled help, and in 1928 they got it. Bruno secured a fake passport and smuggled himself back into the United States. He became the tribe's chief incorrigible, editor of L'Adunata dei Refrattari. In Brooklyn or Queens, secretly, at home, never at the newspaper office, he prepared each weekly issue, wrote most of the copy, did the technical editorial work, then gave the material to a trusted comrade who took it to the printer. And in this manner the work of the antiorgan.

It is hard to remember today - perhaps it has never been widely known - just how magnificent a role was played by Italian-American anarchists from the 1920s until World War II. These anarchists mounted the first opposition to fascism in the United States. Mussolini came to power in 1922 and did not lack for support among Italian-Americans. Il Progresso, largest of the Italian-American newspapers, was profascist. Politicians in districts with large numbers of Italian Americans - a lot of districts trimmed their sails because of Il Progresso. And it was the anarchists who mobilized resistance.

Carlo ‘lfesca - an anarcho-syndicalist, therefore not a Galleanista - was Italian America's leading antifascist. As Norman Thomas once said, 'lfesca's contribution to American democracy was for this reason very great. Perhaps his methods were not always lofty. When Mussolini's American followers called a rally, so did Comrade 'lfesca, and out came 'lfesca's boys, and the boys were a little rough, and Italian-American fascism found that it never could hold a street rally in peace. This did the trick. 'lfesca was vastly more influential in these matters than were Bruno and the Adunata tribe. It would be pleasant to record that Bruno and L'Adunata at least aided 'lfesca in his work. But that was not the case. L'Adunata was extremely sectarian. I've spoken to more than one old anarchist who regarded Bruno as a narrow-minded fanatic. His newspaper denounced 'lfesca as a temporizer, a reformist, a collaborator. It even accused him of being a spy. It was the dog that bit at 'lfesca's heels year after year.

Yet Bruno's Adunata, publishing some 5000 copies a week, did adapt to the new era. It toned down about the class struggle in the United States. Maybe the Justice Department's heavy hand had its effect. Maybe the Italian-American working class, having made some social progress, was no longer receptive to extreme appeals. Maybe the Galleanisti themselves began to notice, without ever saying so, that in a country like the United States, if workers struggled hard enough, they could wring a little democracy out of the system. Maybe the antiimmigration laws stemmed the flow of young hotheads. In any case, for all their bitterness against 'lfesca, the Adunata tribe followed a parallel course. Antifascism became their cause. L'Adunata evolved into a world organ of anti-Mussolini Italian exiles, not all of whom approved the newspaper's specific doctrines. Arturo Thscanini was L'Adunata's reader. And apart from ordinary propaganda, the Galleanisti brought methods of their own to the antifascist cause.

Readers may be dimly aware that

in 1900, still another Paterson anarchist, Gaetano Bresci, returned to Italy

and assassinated King Umberto I, whose forces had massacred workers in Milan.

A Gruppo Gaetano Bresci formed in New York and was a lively center for nice

young people on East 1O6th Street. Unfortunately two members of the Gruppo,

one of whom possessed the Galleani "health" pamphlet, were enticed

by a police agent into plotting to blow up St. Patrick's Cathedral. That

story is known. But the story of Mike Schirru of the Bronx is, I believe,

entirely unknown in this country. Comrade Schirru was one of the Adunata

incorrigibles. In 1931 he served in Europe as L'Adunata's correspondent,

mailing stories back to Bruno under the code name "Kemi" about

a Belgian antifascist trial. Then he went to Rome and tried to blow up Mussolini.

Illogically, Schirru was arrested before the plot could take effect. A firing

squad of 24 men put him to death. His last words were:. "Abbasso it

fascismo!" And, just like Nicola Sacco being executed in Massachusetts:

"Viva l'anarchia!" What was Bruno's part in Schirru's plot? The

noted Italian journalist Giuseppi Fiori wrote a book in 1983 called L'anarchico

Schirru: condannato a morte per l'intenzione di uccidere Mussolini in which

he argued, based on Schirru's correspondence, that Bruno was heavily involved.

On the other hand, D' Attilio talked to Bruno about the Schirru conspiracy

and came away convinced that Fiori exaggerated Bruno's role. Still, there's

no question that Schirru was "Kemi" and Bruno's correspondent,

and no question that, in plotting against Mussolini, Schirru acted according

to L'Adunata's principles. And surely this plot, and Schirru's courage in

the face of the fascist firing squad, constituted a moment fully equal to

Italian-American anarchism's more famous achievement, the sustained display

of personal nobility by Sacco and Vanzetti.

For what

if Mike Schirru had succeeded? The Galleanisti were never fated to succeed,

however. And it's striking and infuriating that, though Schirru was an American

citizen, the U.S. government did nothing for him, no embassy representative

ever visited him in jail. President Hoover never asked clemency of Mussolini,

never offered to take Schirru back to the United States. The city of New

York ought to erect a statue to Mike Schirru, heroic Galleanista, in his

old neighborhood, 187th Street up near Fordham University. The plaque ought

to quote Bruno's eulogy from L'Adunata, which praised Mike Schirru for having

the "grandeur of Brutus." Five years later Francisco Franco staged

a fascist coup in Spain, and again the American Galleanisti went into action.

Bruno's L'Adunata became a world organ for the Italian anarchist contingent

in the Spanish Civil War. This was by no means a small contingent, and since

the Spanish anarchists were themselves the largest and most important of

the antifascist parties in Spain, L'Adunata was one of only a tiny number

of American publications allied with the mainstream of Spanish antifascism.

L'Adunata sent money. It raised troops. Several of the old tribe, more than

a handful, less than a hundred, in D'Attilio's estimate, went to fight,

and some of them died. The paper's correspondent was Camillo Berneri, an

Italian professor and one of the only intellectuals in Spain with influence

in the principal sector of the Spanish labor movement. But Bemeri was murdered

in 1937, almost certainly by a Communist death squad – though that

term wasn't known at the time -and the war was lost and the fate of the

Italian anarchists in Europe was a terrible one.

For what

if Mike Schirru had succeeded? The Galleanisti were never fated to succeed,

however. And it's striking and infuriating that, though Schirru was an American

citizen, the U.S. government did nothing for him, no embassy representative

ever visited him in jail. President Hoover never asked clemency of Mussolini,

never offered to take Schirru back to the United States. The city of New

York ought to erect a statue to Mike Schirru, heroic Galleanista, in his

old neighborhood, 187th Street up near Fordham University. The plaque ought

to quote Bruno's eulogy from L'Adunata, which praised Mike Schirru for having

the "grandeur of Brutus." Five years later Francisco Franco staged

a fascist coup in Spain, and again the American Galleanisti went into action.

Bruno's L'Adunata became a world organ for the Italian anarchist contingent

in the Spanish Civil War. This was by no means a small contingent, and since

the Spanish anarchists were themselves the largest and most important of

the antifascist parties in Spain, L'Adunata was one of only a tiny number

of American publications allied with the mainstream of Spanish antifascism.

L'Adunata sent money. It raised troops. Several of the old tribe, more than

a handful, less than a hundred, in D'Attilio's estimate, went to fight,

and some of them died. The paper's correspondent was Camillo Berneri, an

Italian professor and one of the only intellectuals in Spain with influence

in the principal sector of the Spanish labor movement. But Bemeri was murdered

in 1937, almost certainly by a Communist death squad – though that

term wasn't known at the time -and the war was lost and the fate of the

Italian anarchists in Europe was a terrible one.

Then

the world of L'Adunata began to splinter. The question arose, should the

anarchists support the Allies in World War II or remain neutral, on the

grounds that World War II was a capitalist war? Bruno favored proletarian

armies, as in Spain, where the anarchists fielded their own  militia. But

a capitalist army he could not support. He took the same position on World

War II as he had taken on World War I. This time the comrades didn't entirely

agree. Some of the incorrigibles around L'Adunata were refugees from Mussolini

who were happy to see Il Duce overthrown even by the capitalists. So the

ranks of Italian-American anarchism split. When Mussolini did get overthrown,

L'Adunata briefly revived. Fascism had destroyed the working-class press

in Italy, and comrades in liberated zones imported L'Adunata to fill the

gap. The print run rose to 10,000. But Italian readers, even anarchists,

found L'Adunata a little extreme. The Italian anarchists were generally

in favor of forming anarchist organizations, but L'Adunata's current of

thought was unwaveringly antiorganizzatrice.

militia. But

a capitalist army he could not support. He took the same position on World

War II as he had taken on World War I. This time the comrades didn't entirely

agree. Some of the incorrigibles around L'Adunata were refugees from Mussolini

who were happy to see Il Duce overthrown even by the capitalists. So the

ranks of Italian-American anarchism split. When Mussolini did get overthrown,

L'Adunata briefly revived. Fascism had destroyed the working-class press

in Italy, and comrades in liberated zones imported L'Adunata to fill the

gap. The print run rose to 10,000. But Italian readers, even anarchists,

found L'Adunata a little extreme. The Italian anarchists were generally

in favor of forming anarchist organizations, but L'Adunata's current of

thought was unwaveringly antiorganizzatrice.

Bruno kept L'Adunata going until 1971. The column on the last page was called "Cronaca Sovversiva," just to underline the continuity with the journal that Luigi Galleani founded in 1903. But judging from the pages I've studied, dictionary in hand, L'Adunata was not at all out of step with modern event. Leafing through the early 1960s, I found Bruno's commentary on Fidel Castro's rise to power to be quite astute. Bruno left no question that Fidel was a dictator. That was the anarchist line. Vanzetti said back in the 1920s, "The Bolsheviki leaders' dictatorship is an increased perfectioned exploitation of the proletariat." But Bruno went on to worry about the propaganda campaign against Castro. Wasn't its purpose to serve U.S. imperialism? L’Adunata had readers in Argentina and other Latin American countries, and Bruno wrote frequently and sympathetically on Latin topics. I stumbled across his observations about General Somoza, dictator of Nicaragua. L'Adunata was scathing about General Somoza.

There were commentaries by Bruno and one of his correspondents, Dando Dandi, on the American civil rights movement of the 1960s. The American civil rights movement had a militant friend in the Italian-American weekly newspaper, L'Adunata dei Refrattari. And L'Adunata cultivated a very pure Italian prose. The respected comrade Valerio Isca, L'Adunata's faithful reader and political critic (from the perspective of anarcho-Thoreauvianism), tells me that however irritating Bruno's Galleanista politics may have been, his newspaper published the best prose of any other paper in the United States. Bruno's style was unimpeachable.

Of course the readers were increasingly aged. Young people didn't subscribe. Perhaps there was something about the old Galleanisti that prevented them from handing along much of a legacy. In the middle 1970s, when the New Left was falling apart, a number of student radicals used to show up at meetings of the old-time anarchists in New York and other cities. I remember well the New York talks held by the Libertarian Book Club at the Workmen's Circle Center. We students used to go because we liked to hear the old anarchists call down all the curses of heaven against capitalism, and because' we admired the old folks for their libertarian spirit, and because they hated the commies and Leninists, and because brilliant and original things were sometimes said, and because... well, perhaps because we noticed that some of those ancient comrades were, in their different ways, saints. There was a glow about them. They were ennobled by their ideal.

They talked about justice for the working class, about their aspiration to

combine socialist equality with complete, limitless individual freedom, and

those old people were radiant with the beauty of their own ideas. Those old-time

anarchists were mostly Jews and Italians. I did think the Jews tended to be

a tad more flexible. The old comrades who used to publish the Freie Arbeiter

Stimme, Jewish-language equivalent of L'Adunata dei Refrattari, were pro-trade

union. They had built some of New York's best cooperative housing. Some of

them were so flexible they had practically become liberals. They were, so

to speak, anarcho-social democrats, which was a very intelligent thing to

be, I came to think. Certain of the old Italians had gone the same way. But

not all. I know that Bruno sometimes showed up at New York meetings, though

I never knew which of several dignified elderly men he was. L'Adunata had

ceased publication, but its editor kept busy. He wrote obituaries for anarchist

newspapers in Italy. As recently as 1982 he came out with a book, which he

worked on with D'Attilio. It was the English translation of Galleani's opus,

The End of Anarchism, with an introduction by "Max Sartin," a/k/a

Bruno, a/k/a Raffaele Schiavina. And no, Bruno was not sliding toward social

democratic liberalism. The book that he translated was precisely a diatribe

against anarchists who become social democrats. It was a call for militant,

individual, revolutionary action. Chapter Seven, "Propaganda of the Deed,"

offered one of the most rapturous endorsements of assassinating tyrants that

anyone has ever written in the United States. The chapter extolled tyrannicide

on practical, moral, political, and aesthetic grounds. You can imagine that

Mike Schirru read this book, in its original Italian, before setting off to

blow up Mussolini. Bruno said in his 1982 introduction: "Galleani's little

book will be of great help today, tomorrow, and forever, until the total emancipation

of mankind from the scourges of oppression, exploitation, and ignorance are

erased from the face of the earth." Raffaele Schiavina, Bruno - was a

mountain of anarchist stalwartness. The movement that Galleani created, the

movement that generated Sacco and Vanzetti, whose struggle was one of the

most inspiring that American justice has ever seen, the movement that sent

Mike Schirru to Italy on his heroic mission, that sent money and men to fight

against Franco in Spain-that movement, narrow, visionary, crazed with idealism,

dangerous, noble, lyric, impossibly brave, has now lost its last standard-bearer.

In the book that Bruno helped translate, Galleani said the anarchists must

pass the torch and the axe to the eager hands of the proletariat. The torch

and the axe have now been put down.